When it comes to vocabulary, having some proverbial elbowroom in which to flex your verboseness provides a great deal of security in the arts of writing and locution. After all, one only runs out of things to say when they run out of ways to say them and saying them with the same droll, repeated words makes for unengaging interactions.

Of course, it’s easy to stick to and never deviate from the established vernacular zeitgeist when meeting up with your friends over lunch or at the local sock hop[1], but if you want to stand out from the crowd in spectacular fashion and expand your modes of thought, you got to learn the lingo to do so.

So, in no particular order, here are 11 words to add to your literary corpora and colloquies:

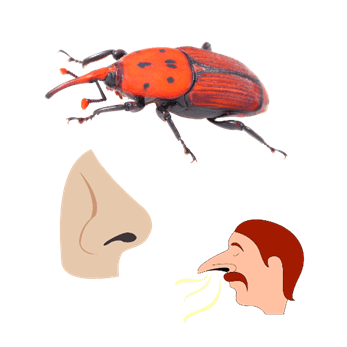

11. Schnoz (sh-nozz)

A fun slang word to describe the nose, especially if you want to draw attention to its size. The short form of schnozzle/schnozzola, Schnoz,is silly in nature and often used to poke fun at the shape and dimensions of a large, elongated nose of either a human or an animal.

Originating in the U.S. between 1935-40, schnoz is a likely amalgamation of the German schnauze (‘snout’), Yiddish shnoitsl, and Middle English snute/snoute (‘snout’).

Consider this clever use of schnoz in an article from Popular Science:

“The frog’s most distinctive feature is a long, protruding snout resembling that of a tapir, a pig-like, hoofed mammal with a distinct trunk. The shape of the frog’s schnoz may hint at a life spent nosing through soft, wet soils.”

– (Baggaley, 2022)

10. Garrulous

“For a time, too, I dropped out of the garrulous literary and journalistic circles I had frequented.”

– The New Machiavelli, H.G. Wells

Garrulous describes someone who talks much about nothing meaningful; a conversational meanderer that rambles on in a roundabout manner about rambling on in roundabout manners.

To speak garrulously is to speak excessively in an overly wordy manner and garrulity is a quality frequented by gossipers of the lowest standards.

Garrulous found use in the 1610s and stems from a variety of languages, including first/second-declension Latin garrulus (talkative, chattering), Greek gerys (voice, sound), Ossetic – an Iranian language – zar (song), Welsh garm and Old Irish gairm (noise, cry).

So, the next time a friend starts babbling on, tell them to quit being so garrulous and watch in amazement as you’re met with stares of impertinent incredulity.

9. Querulous

“A good conversation always involves a certain amount of complaining. I like to bond over mutual hatreds and petty grievances.”

– Christmas Eve at Friday Harbor, Lisa Kleypas

People who are quick to complain given the chance display querimonious intent and are characterized by their querulousness. Petulant and peevish, they’ll habitually find a wry remark to make or a fault to point out. Think of querulous as a prelude to quarrelsome.

Stems from 1400s Old French querelos (argumentative) and Late Latin querulosus (full of complaints).

8. Cantankerous

“A bookstore is one of the few places where all the cantankerous, conflicting, alluring voices of the world co-exist in peace and order…”

– Jane Smiley

Take a look at this kitty; doesn’t look at all agreeable, does he? As if whatever you ask of him will be met with a resounding ‘no’ despite any amount of charismatic persuasion or sound reasoning. This kitty is cantankerous, a contentious and disagreeable sort who goes against any ideas or suggestions put forward.

Cantankerous is related to cranky, dour, prickly, contrary, and huffy. It found life in the late 1700s thought to be derived from 1300s Middle English contakour (troublemaker), which itself is derived from Anglo-French contee (discord, strife), which is even further derived from Old French contechier.

7. Lummox

“Don’t you dare go up there, you big, long-legged lummox!”

101 Dalmatians, 1961

Lummox describes a person who is clumsy and lacking in articulation, awkward.

Lummox found its way into the English language around 1825 as East Anglian (primarily Norfolk and Suffolk of the UK) slang of unknown etymological morphology, my money’s on a portmanteau – or joining – of ‘lumbering’ and ‘ox’.

6. Lachrymose/Lachrymal

“Tears are curious things, for like earthquakes or puppet shows, they can occur at any time, without any warning and without any good reason.”

– The Wide Window, Lemony Snicket

We all, each of us, get a little lachrymose from time to time, that is to say weepy. Lachrymosity is the state of crying or being inclined to cry; a useful vocab addition for any romance writer or dramatic persona out there.

Originating in the 1660s, lachrymose stems from Latin lacrimosus (tearful, weeping) and lacrima (a tear), which is related to the Greek Δάκρυα (‘dakrya’ – tears).

5. Brobdingnagian (brob-ding-nag-ee-uhn)

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

– Ozymandias, Percy Bysshe Shelly

Without its etymological context, Brobdingnagian (note it’s always spelled with capital ‘B’) is perhaps one of the most perplexing ways of describing something as gigantic.

Brobdingnagian comes from the word Brobdingnag which was an imaginary country where everything was of a gigantic scale, coined by Jonathan Swift in his 1726 novel: Gulliver’s Travels.

Other such words attributed to Swift (or Swifties as they’re lovingly called) include our next entry; houyhnhnm (hoo-in-uhm), which signifies a horse, also from Gulliver’s Travels; modernism; spargefaction, which is the act of sprinkling; truism; the name Vanessa; and Yahoo, again from Gulliver’s Travels.

4. Lilliputian

“It was all cherry satin and white lace, the furniture Lilliputian…”

– Ancestors, Gertrude Atherton

Whereas Brobdingnagian is used for the immense, Lilliputian (always a capital ‘L’) is used for the opposite: the tiny or trivial.

Another word from Gulliver’s Travels, Lilliputian derives from Lilliput, an imaginary island in the novel whose inhabitants were extremely small.

3. Zebrine

“In an occasional horse the long-lost stripes of the zebra-like ancestor reappear.”

– Man and His Ancestor, Charles Morris

Ever had the specific need to describe something as zebra-like but couldn’t think of another word? I introduce you to zebrine, a quixotic word I didn’t know existed before writing this article and one that will surely eliminate many a hyphen from many a bespoke description of stripy or diametrically opposed things in my future writing.

Zebra comes from 1600s Italiano and was earlier applied to a now-extinct wild ass of uncertain origin. Zebrine is a likely combination of zebra and equine (of horses).

2. Prosopopoeial (pro-so-po-pee-ahl)

“The iron tongue of midnight hath told twelve:

– A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare

Lovers, to bed; ’tis almost fairy time.”

Prosopopoeia is a figure of speech where an imaginary or absent person is represented as speaking or acting, also the personification of inanimate things. Think of any anthropomorphic Disney character or cartoons where the kitchenware holds conversation. Using prosopopoeial allows you to separate the message from the message-bearer be they real or otherwise.

1560s, from Latin prosopopoeia, from Greek προσοπωπεία (prosōpopoiia, “the putting of speeches into the mouths of others/personification”).

1. Sesquipedalian (ses-kwih-peh-dale-ee-an)

“Voila! In view humble vaudevillian veteran, cast vicariously as both victim and villain by the vicissitudes of fate. This visage, no mere veneer of vanity, is a vestige of the “vox populi” now vacant, vanished. However, this valorous visitation of a bygone vexation stands vivified, and has vowed to vanquish these venal and virulent vermin, van guarding vice and vouchsafing the violently vicious and voracious violation of volition.

– V for Vendetta, Alan Moore

The only verdict is vengeance; a vendetta, held as a votive not in vain, for the value and veracity of such shall one day vindicate the vigilant and the virtuous.

Verily this vichyssoise of verbiage veers most verbose, so let me simply add that it’s my very good honour to meet you and you may call me V.”

Sesquipedalian refers to the quality given to excessive use of long words or long-winded phrasing containing many syllables.

Also related to sesquipedalia is the ironically named hippopotomonstrosesquipedaliaphobia, which is the fear of long words.

Fun Fact: the longest known word in English is the chemical composition of the protein titin, consisting of 189,819 letters and taking between 2-3 hours to pronounce.

Sesquipedalian dates from the 1610s, from Latin sesquipedalia (“a foot-and-a-half long”). The sesqui- means “one and a half” and is found in other words such as sesquicentennial (150 years), or chemical compounds indicating a ratio of 2 to 3: sesquioxide, sesquiterpene, sesquicarbonate.

References

Baggaley, K. (2022) Behold, the tapir frog’s magnificent snout, Popular Science. Available at: https://www.popsci.com/animals/tapir-frog-new-species/ (Accessed: 05 December 2023).

Tung, A. (2014) 8 words coined and popularized by Jonathan Swift, theweek. Available at: https://theweek.com/articles/441971/8-words-coined-popularized-by-jonathan-swift (Accessed: 08 December 2023).

Appendix:protologisms/long words/titin (no date) Wiktionary, the free dictionary. Available at: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:Protologisms/Long_words/Titin (Accessed: 08 December 2023).

Most etymological notes on the words here have been acquired from: https://www.etymonline.com/

[1] Mid-20th-century nomenclature for a disco.

Leave a comment