Passwords are the proverbial bread & butter to any sound security strategy aimed at protecting access to our digital data and consequently, one of the most prominent threat vectors potential hackers will target.

In this article, we take a brief look at various types of password attacks and security considerations.

Types of Password Attacks

Password attacks can range from simply guessing a password until successful or watching someone enter their password, known as ‘shoulder surfing’, to the more technical approaches like keyloggers, pre-computing password hash values, or carrying out sophisticated phishing campaigns. We’ll look at some of the different methods used to discover and attack passwords, as well as best practices for safeguarding against them.

Cracking, Brute-Force, & Dictionary Attacks

Password cracking or “recovery” tools such as John the Ripper or Hashcat can be used to repeatedly guess a password until discovered.

Think of a 4-digit PIN code. There are a total of 10,000 possible PINs, 0000 – 9999. Even low-end computers can try every PIN combination in this range in a matter of milliseconds, for a real-world example check out this article from Ars Technica of a computer cluster able to guess 350 billion passwords per second.

To make passwords harder to guess, we increase their length and complexity. Going back to our 4-digit PIN example, using only the numbers 0-9 we get 10,000 possible PINs, or 10 possible values per digit (10*10*10*10 = 10,000).

If we increase this to a 5-digit PIN, we increase the number of possible PINs exponentially, that is, the number of possible characters c we can use per digit exponentiated by the length l of the PIN/password (c^l), or in a 5-digit case, 10^5 = (10*10*10*10*10) = 100,000.

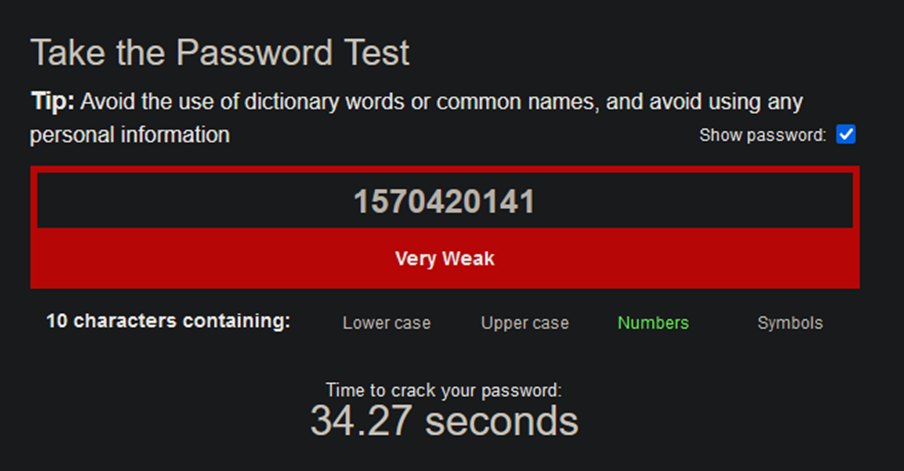

We could continue to add more digits to our PIN, but this is inefficient and unwieldy, consider this example with a random 10-digit PIN:

In addition to length, we add complexity to strengthen our passwords. Complexity involves diversifying input so there is a greater range of characters used. For example, if we add lower-case a-z characters to our 5-digit PIN, we now have 10+26 (letters of the alphabet) = 36 possible values per position, or 36*36*36*36*36 (36^5) = 60,466,176 possible passwords, a whole lot more than 100,000.

Note: Although the above seems like a strong password, with ever-increasing computing power and the advent of distributed/cloud and quantum computing, using only a mix of digits and lower-case letters in a password should be avoided.

As you can imagine, trying literally every single combination of characters is a crude and potentially time-consuming process, for this reason, pure brute force attacks aren’t the first choice outside of short and simple passwords.

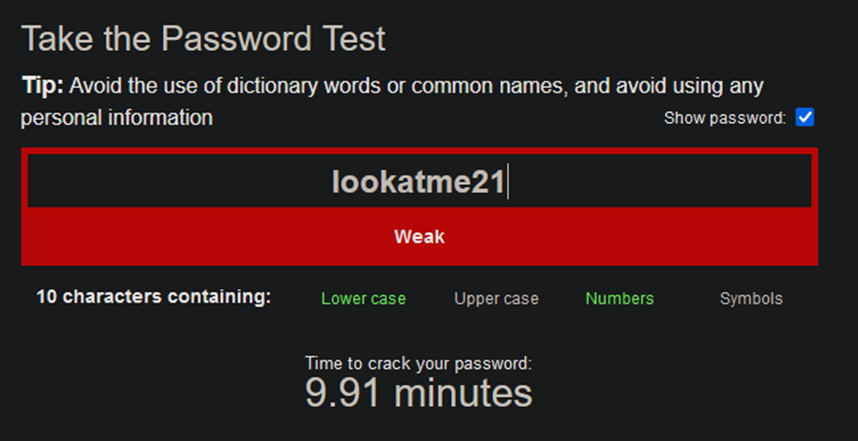

Efficient cracking boils down to knowing something about the structure of a password. For example, people are more likely to use a word in a password instead of a random selection of letters and numbers, this means some of the difficulty can be bypassed as instead of brute-forcing every possible combination of letters and numbers, an attacker could brute-force different combinations of words. This more sophisticated implementation of brute force attack is known as a Dictionary Attack and can significantly reduce the amount of time to crack. This also extends to artistic variations on words e.g. l00k@m321

Protecting Against Cracking

Somewhat counterintuitive, the key aspect of defence against password cracking is not by having the longest, most complex password feasible – it is the time it takes to crack it and adding length/complexity simply increases that length. Theoretically, no password is truly hidden, if you run a brute force algorithm you will eventually discover any password; however, if the timeframe of ‘eventually’ is something like 3 million trillion years, we can be fairly sure of a password’s resilience, for the moment anyhow.

In addition to length and complexity, an efficient deterrent against cracking attempts are Account Timeout and Account Lockout policies. These are deterrent controls which encumber cracking attempts by enforcing for example, a 5-minute wait timer or complete account lockout after 5 incorrect password attempts. This effectively reduces the number of guesses an attacker can make and often alert administrators to a potential attack.

Rainbow Table Attacks

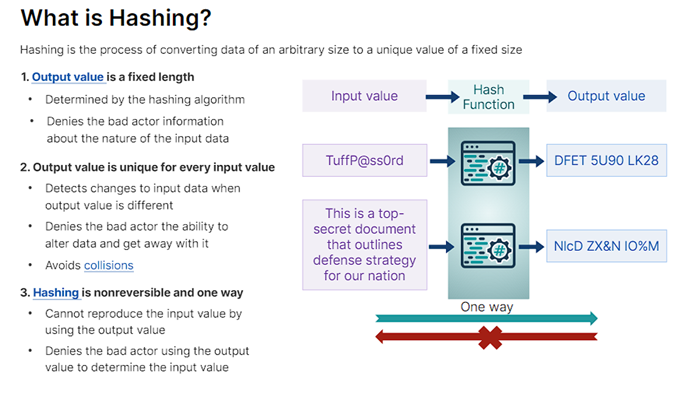

Another form of password cracking is the use of pre-computed hash values to match the hashed output of a given password, compiled into something known as a Rainbow Table.

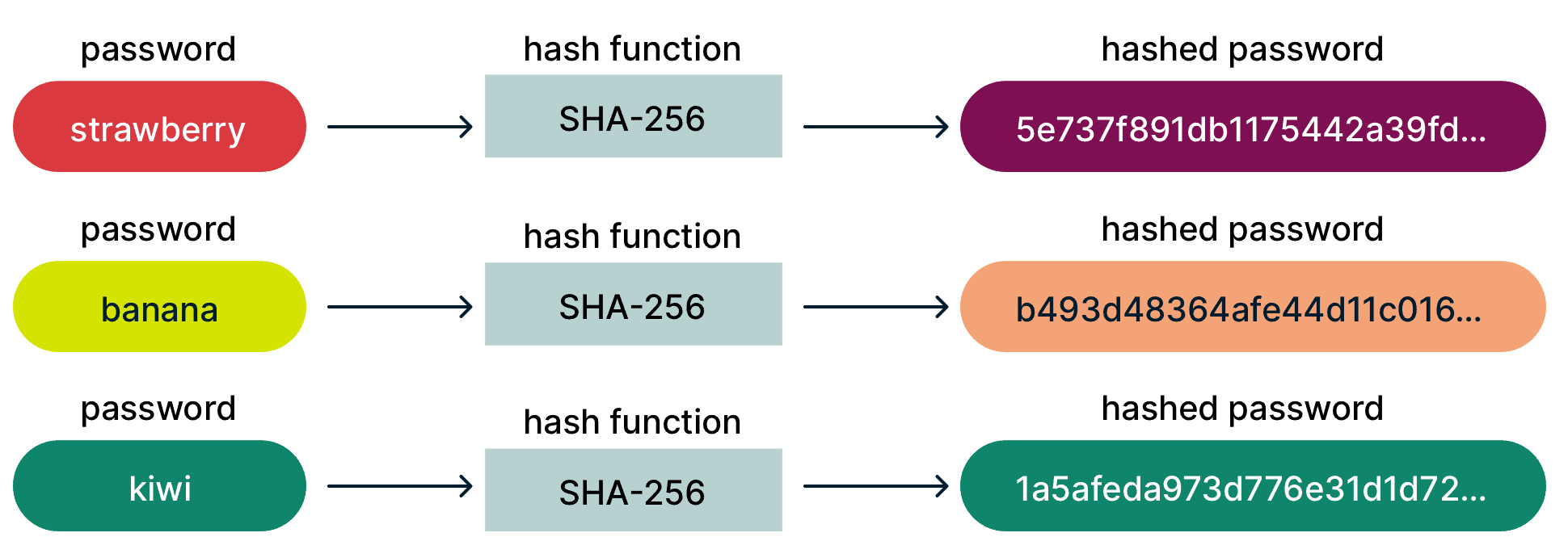

Hashing is the process of taking information of any length and jumbling it up into an output of fixed length to obscure it, if you enter the same input, you always get the same output.

Typically (hopefully), when you create a password for an online account such as Google, it is fed into a hashing algorithm, such as SHA3-256, and this hashed output is stored in a secure database. This means that if the password database itself is compromised, attackers cannot immediately see the text of all passwords used, they only see the jumbled hash outputs.

However, this isn’t fool-proof protection. Recall that hashing an input always produces the same output, so if the hashing algorithm used is known, hashes can be ‘pre-computed’ by mapping every possible input to its equivalent hashed output.

If a database was leaked and one of the hashes was c24a542f884e144451f9063b79e7994e for example, and the hashing algorithm was known to be MD5, attackers could simply keep hashing potential passwords with MD5 until they find a match, in this case c24a542f884e144451f9063b79e7994e maps to the text password12. Often, attackers will generate or buy large rainbow tables to ‘sweep’ across credential databases to discover as many logins as possible.

Another part of this is the concept of hash collisions, which occur when different inputs produce the same hashed output, meaning an attacker doesn’t necessarily need to use a specific input, only find some input that produces the same hashed output.

To safeguard credentials, service providers employ a range of mitigations which may include:

- Using secure hashing algorithms which produce lengthier outputs to help reduce collisions – more info on secure hash algorithms can be found on the NIST website.

- Add further complexity by salting (adding random values) the input to be hashed.

- Employ additional layers of protection such as MFA and VPNs.

What you can do as a user to add security:

- Avoid using the same password/similar variations of a password for multiple accounts. If one of your passwords are compromised, the next logical step an attacker will take is trying that same password or similar variations on all your other accounts.

- Update and change your online passwords at least once a year. Companies can be notoriously opaque when disclosing they’ve suffered a data breach, regularly changing passwords can mean that by the time an attacker compromises them (from known/unknown data breaches) they’re unusable – if you come across news that a service you use has suffered a data breach, change your password immediately.

- Avoid services and companies relying on weak/outdated data security practices and hashing algorithms like MD5 for authentication.

Phishing

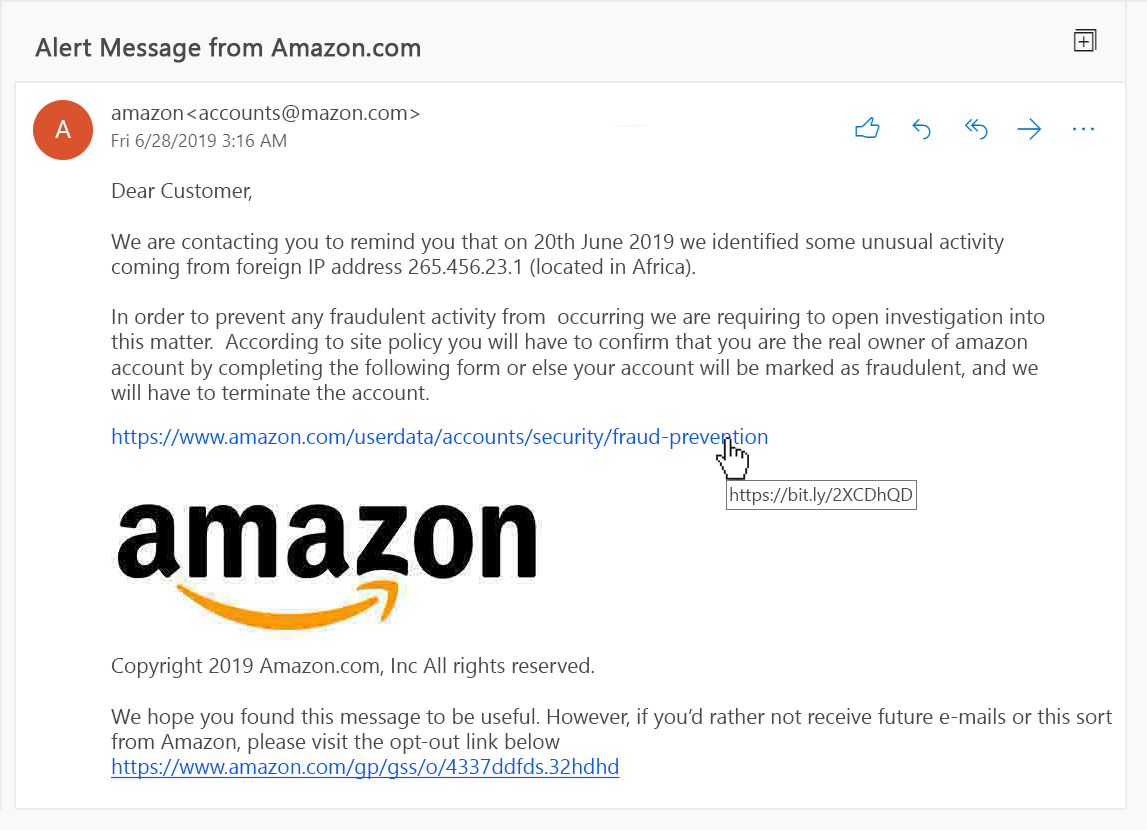

The scourge of email communication, phishing, falls under the umbrella of Social Engineering and is an attempt to steal information whereby an attacker constructs a seemingly legitimate email (or in the case of smishing, a SMS message) to trick someone into clicking a malicious link or entering their login credentials to a fake website. While primarily meant to steal information, phishing can also be used to trick you into installing malware/viruses on your device.

Remain vigilant to any signs of suspicion within your emails, always check for:

o Sudden urgency or unusual requests: One of the biggest red flags to look out for is an email conveying a sense of urgency to take some action. These methods rely on a perceived negative outcome if quick action isn’t taken, such as account lockout, monetary fines, etc. Some classic examples include:

- An email from your ‘bank’ saying your account is compromised and you must login via the link provided to fix the problem.

- An email/SMS from a delivery service like Amazon or your post office saying there are unpaid customs charges or delivery fees for a package.

o Unusual sender email address: If an email raises suspicion, look at the sender’s email address. Often attackers will leverage or spoof a legitimate email domain to give the illusion of authenticity, e.g. using a fake address of accounts@ƅumble.com (<- notice the ‘b’) posing as accounts@bumble.com

o URL Mismatch: Think of a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) as a link to a web address on the internet, such as https://makefrontendshitagain.party. The blue text you see on screen isn’t the link itself, it simply describes it; rather, the link is embedded ‘behind’ the text, processed by your web browser, and you can see this when you hover (or hold if using mobile) it. Try hovering over the following link and note where it will really send you: https://thisiswhereyouwanttogo.com – attackers use similar tactics to send you to fraudulent websites by placing the text of a legitimate website name and embedding a malicious link behind it. With suspected phishing emails, always double-check exactly where a link will send you before you click.

o Impersonal or generic greetings, especially in sensitive matters: e.g. an email addressing “Dear User” instead of your name or username. A company will have access to any information you provide at account registration, attackers may not and so often opt to use blanketed greeting terms like ‘user’ or ‘customer’.

o Check for the use of poor or unusual grammar/spelling mistakes: With the advent of AI language models this should now incorporate overly-formal, friendly, or structured text/greetings.

o Be wary of engaging with any unsolicited emails or cold calls claiming to improve your SEO or service. If it seems too good to be true, utilize your email’s flag and block options.

Shoulder Surfing & Plain Sight

An often-neglected form of password discovery is an attacker simply eyeballing it, whether by watching someone type their password in or if they have the poor practice of writing their passwords down and sticking them to the monitor (this is more common than you’d think).

A preferred method over writing your passwords down is to use a password manager app. This is essentially a personal vault to store all of your passwords and provides various tools for creating, tracking, and autofilling. Using a password manager has its own considerations and we will discuss this in more detail in the next article.

Take note of your surroundings when entering sensitive information. Privacy screens can help mitigate shoulder surfing by obscuring the view at an angle, requiring an onlooker to be directly behind you to see information on your screen.

There are a whole range of other methods to steal passwords, including keyloggers or screen capture malware. As a basic precaution: maintain a trusted, up-to-date antivirus, remain vigilant, and don’t download random stuff from the internet!

Conclusion

For most people, a username and password combination are the first and last lines of defence against unauthorized access of an account or data; the security and secrecy of these are paramount.

In the next article, we’ll dive deeper into the aspects of password security, including how we can generate strong, manageable passwords with the use of password managers, using MFA to provide additional layers of protection, and explore the modern trends of single sign-on (SSO) and ‘passwordless’ authentication.

~ G.G. May 2024

Leave a comment